When we are physically or mentally unwell, we visit a doctor. We walk into their office hoping, even expecting they can fix all our problems and help make us better. And most of the time, they really do!

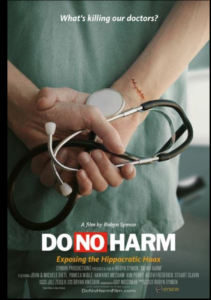

But let’s change the scene for a few minutes. There is another story worth telling that often goes unspoken.

What about the doctors themselves?

When Does the Doctor Need Help?

If you are a doctor and you are now feeling that you have had enough of the stress, the long hours, the sacrifices considered normal in the medical profession, the toll it has taken on your relationships and your health, the threat of burnout, where do you go? What if your professional success has come at a high cost or maybe you seek that elusive personal fulfilment in a direction different from your colleagues, who do you talk to?

Doctors go through highly rigorous education and training, both pre and post-graduation, and work and train and study over longer and more intense hours than most people realise. To make matters worse, the amount of responsibility on their shoulders is insane and increasing rapidly, while the public tolerance for error is reducing at the same rate. The personal cost of burnout is no less significant than the societal cost in the community they serve.

Medics are often perfectionists; we have to be. And perfectionists suffer in an imperfect system in an imperfect world.

Surgeons, Anaesthesiologists, emergency medical physicians to name just a few, carry this burden of perfection. They continually strive for excellence knowing they cannot afford to make a mistake – there are human lives at stake.

But being a doctor doesn’t erase the fact you are human too. You are human first and foremost.

And humans make mistakes. Everyone does at some time or another. Why do you think nurses are doubly counting the number of gauzes and sutures used for an operation? Why do Pharmacists double check your prescriptions? Because we are all constantly at risk of making a mistake – and some mistakes are more critical than others.

The question is, do you, as doctors, accept that you can make mistakes? Can you accept the reality that a mistake could find its way into your hands, sooner or later, and that you will need to accept the consequences that that mistake will bring?

Perfectionism, while admirable and worthy, is unattainable despite how many letters you have after your name. Learning to accept that you, too, despite your best intentions, and professional competencies, can indeed make mistakes, is far more important for your own health and wellbeing.

But what do you do if you find it difficult or impossible to accept that you made a mistake?

How do you move on? How do you avoid letting that mistake, or fear of making another one, add more stress to your already stressed life?

With all your education and experience, you drive on. You may refuse to admit something is wrong. You will continue pushing, working, keeping your head up like nothing is happening. Until your mind and body give up! It doesn’t have to be this way!

You ask for help.

Doctors, Ask For Help, Please.

Fortunately for me, I was relatively unscathed by my career, and I wouldn’t change it for the world. There are many beautiful and altruistic reasons why one decides to become a doctor, or any other medical or allied health professional. These reasons don’t disappear when you are going through a difficult time, yet they can get lost in the overwhelm.

So, there is a problem worth talking about.

A recent study in the US showed that 28 to 40 physicians out of 100 000 commit suicide. Even though there is enough international data, little is done about it. For example, Ireland doesn’t have official data at all. Does that mean doctors in Ireland don’t commit suicide?

Of course it doesn’t. It is just that doctors are viewed by other people (and themselves) as some other form of life, immune to the effects of dealing with the relentless human suffering of others.

It is highly likely you know someone who died by suicide. They were a colleague, or a colleague’s friend, maybe just an acquaintance from another hospital or those beloved medical conferences.

You saw them once or twice and then you read about their self-imposed, and way too soon death. So what do you do? Maybe you talk about it with your colleagues, but do you ask yourself the hard questions? What are you ignoring, resisting or avoiding?

It is human to ask for help, so why don’t doctors look for advice on how to improve or change their own lives for the better?

Let’s talk about the fact that doctors are humans, and humans have problems. We make mistakes, we need support and we must ask for help when we need it.

A final note.

I practised medicine for 32 years, across multiple specialities, in several countries. It’s now when I see my colleagues suffering, all around the world, that I am sounding the alarm bells.

Especially with what we are witnessing during this pandemic when so many of our resources have been overwhelmed. It was bad enough pre-Covid, now it’s a crisis!

I am not a psychiatrist or a therapist, so I cannot help you with serious mental issues like depression but perhaps I can help you find a path that will put you back on the road to wellbeing.

Our “problems” are not going away. It’s time to find a more constructive way of dealing with them.

Even without an operating table in a hospital, my message stays the same – Wake Up!

Wake Up to Wellbeing.

Physician, Heal Thy Self.

Be a human; Ask for help.

Love and Light

Eileen